|

By Rohit Brijnath |

|

|

By Rohit Brijnath |

|

![]() ear

ago, an Indian hockey player, capped almost 100 times for his country, attended a

function hosted by the company he worked for. For a while his colleagues were

flattered by his presence. But soon, their attention was diverted to another guest

who had just arrived, leaving the hockey player to shake his lonely head in dismay.

ear

ago, an Indian hockey player, capped almost 100 times for his country, attended a

function hosted by the company he worked for. For a while his colleagues were

flattered by his presence. But soon, their attention was diverted to another guest

who had just arrived, leaving the hockey player to shake his lonely head in dismay.

The man who had just usurped his moment was a cricket player. Not even one who had represented India, but just a Ranji Trophy player.

When the player told this story, part of him believed that the culprit for his anonymity was the game of cricket. The more hysterical the worship of this demon sport, the lesser the time for others.

Is cricket the villain?

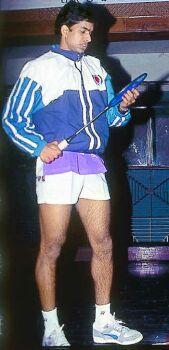

Indian cricket team for the 1996 World Cup

Photograph by S. Patronobish for Sportstar

For other sports, cricket makes for a perfectly disreputable villain. Many sports would rewrite their rules if they could seduce sponsors, yet cricket is dismissive of anyone whose cheque contains inadequate zeroes. Most Indian sportsmen grovel in anonymity, yet cricket's stars smirk at us from billboards, television sets and newspapers.

Other sports have much to be envious of. Tennis players must win to earn money; cricketers are paid handsomely win, draw or lose. Women's hockey players must carry buckets to training in search of water, cricketers don't even have to share water in their five-star hotel room with another player.

Sports in the rest of the world

Unquestionably there is a lopsidedness in the Indian sporting universe, though this is hardly a unique phenomenon. Hockey players cannot compare with cricketers in Australia; tennis is irrelevant in Brazil when it comes to football; and soccer in the United States is still struggling for survival while baseball and basketball salaries become increasingly vulgar.

In India, the disparity in sports is most conspicuous. Alas, this is not China where one can presume most sports get equal patronage.

In India, sports must fight each other for an audience and money; cricket has cornered the market. Cricket in India appears as a Fortune 500 company when compared with other sports. The explosion of the game across India has been a product of chance, greed and financial acumen. Cricket has understood money.

Hosting the World Cup in 1987 was useful; fighting to bring it home again in 1996 was pivotal. One-day cricket got spread out across small centres and it mushroomed, a circus nourished by the advent of cable sports channels. Television brought exposure, rights moneys and heroes, and sponsors elbowed each other out of the way to be part of the revolution. Once the team was not worthy of all the attention, but now it is.

Cricket was lucky, for it had limited opposition. It is easy to be third best in the world, for instance, when the world is only 10 nations; in football there are 200 countries to contend with. Cricket was fortunate, for top teams routinely arrive at our shores, world class contests routinely unfold before our eyes. Federer is not likely to visit here, neither is Real Madrid.

Amateurism in other federations

Cricket is not at fault for the amateurism that infects its peers. Too many other sports federations are run by old and tired minds, unable to embrace the future and prone to carp about ill-luck. Corruption exists and lethargy runs in their veins.

Cricket adapted to change, and India has become its commercial capital. Not so with other sports. Once hockey filled stadiums and India was constantly in contention at major events. When the shift was made to artificial surfaces in the late 1970s, the change was met with grumbling, and time was spent whining about Western conspiracies rather than focussing on an Indian future. An established tradition was let go, while new tactics and techniques passed us by. Retrieving greatness can be harder than we think.

In the past 10 years, hockey coaches have been cast aside like cheap suits at every turn, and the recent controversy over Dhanraj Pillai suggests a continuing confusion. Even then, Indian hockey has had some highs in the recent past, like the 1998 Asian Games and the 2001 Junior World Cup, but has not known what to do with it.

At moaning, Indian hockey is world class.

Sports have become fiefdoms for politicians and officials who have little concept of modern sport. A minister said after a recent Olympics that India would soon win a host of Olympic medals. But no one knows how.

Football had a sizeable following, and in the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, India finished fourth. Thereafter India has mostly stood still as the world marched by. Whose fault is it that China is at the World Cup, and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, but not India? Who's responsible if an Iraqi team, which does not have the luxury of playing matches at home, qualifies for the Athens Olympics but India does not!

In the mid-1990s, for instance, India was presumed to be a powerful force in women's weightlifting, with lifters routinely returning from championships with medals. Even better, it was a new sport with no real established powers. Opportunity looked India in the eye but it blinked, the sport descending into a chaotic muddle of unseemly politics and drug-taking. Now, not a single Indian contender exists.

Other sports have had heroes, men to build dynasties around, or at least kick-start revolutions. Badminton had Padukone; tennis in recent times had Ramesh Krishnan and Leander Paes and Mahesh Bhupathi; athletics had a superb 1982 Asiad to build on. Chess, to an extent, has ridden wisely on the back of V. Anand. The others have not. Anju George, India's only world-class athlete, recently decried the absence of scientific back-ups; surely her status, and the arrival of an Olympics, suggests she deserves them.

Facilities are not always cutting edge in India, but then again Ethiopia might say the same, and the old Soviet states may say the same, yet champions are produced by them. If athletes in India lack sponsors and must work other jobs, then it hardly makes them unique. Across the world, even in Australia, many Olympic hopefuls must work in shops and supermarkets to sustain themselves. Poverty is a universal burden for athletes.

Role of the Indian media

Photo courtesy The Hindu Photo Library

There is something wistful, and tragic, when All-England champion P. Gopi Chand says, "I am well known in Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, but not in my own country." For this, all of us in the media are somewhat culpable. For newspapers and television in India, cricket is the only sexy story.

"The media was never a source of motivation for me, it has been a let down," says Gopi Chand. He cannot be argued with. We were there to celebrate his crowning, but invisible during his rise. If we were surprised by his feat at winning the All-England, perhaps it was because few had cared to discover how good he was. The daily grind of most sports is often ignored.

Truth is, sports correspondents will spend two hours waiting in hotel lobbies for some pimpled cricket debutant to show up, yet not take the time to walk down the road to where Gopi Chand might be playing, or Anju jumping. In that we do them a disservice.

As an Asian Games star once mentioned, "You guys remember us only once every four years." Arjun Atwal's qualification for the US PGA Tour, for instance, is exceptional, yet barring brief mentions in the sports pages he does not merit much ink.

As much as this is true for the media, it is for the public. Few fans choose to enter stadiums to support other sportspersons. Cricket has settled in the mind and leaves little place and time for other pursuits. As a nation we are guilty of a one-track mind.

The common man as a sports fan

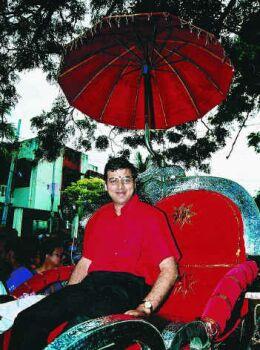

Photograph by M. Moorthy for Sportstar

Years ago, in a column, I wrote about the time when Vishy Anand, just crowned world champion, had returned home to Chennai. Of all the celebrations that greeted his arrival, I asked him what moment stuck out the most.

In answer, he spoke about the day he was being taken out across Chennai in a horse-drawn carriage. Suddenly a bus on the other side of the road screeched to a halt. The driver opened his small door and leapt out. He ran across the road, hurdled the dividing railing, and raced to Vishy and shook his hand.

It was the hand of ordinary India, and it is what other Indian sportsmen look for. It is a hand extended often only to cricketers.

For this, cricket itself is not at fault. Perhaps, in a way, everyone and everything is.

Article courtesy Sportstar, June 5-11, 2004